In the What Works Team we often throw around terms like ‘quasi-experiment’ and ‘meta-analysis’ that can seem quite bewildering at first, but actually describe common-sense approaches to designing and testing policies.

This article is the first of our ‘What Works 101’ articles, describing the basic tools used and recommended by What Works. We’re trying to make these articles clear and interesting and we want to hear what you have to say, so please do comment below!

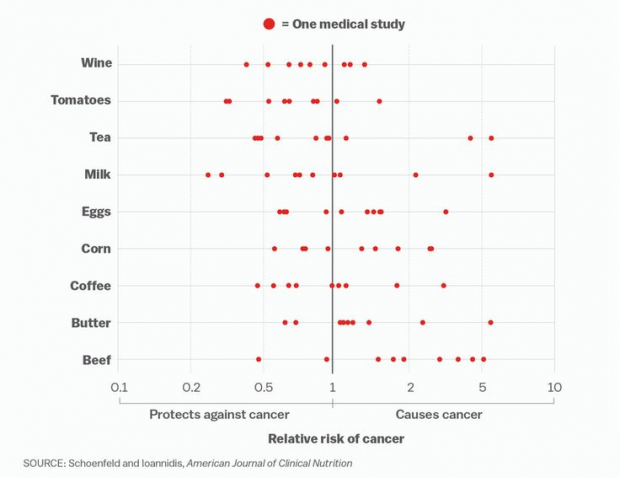

It might come as a surprise to learn that one of the most common challenges to evidence-based policy is too much evidence, but it’s completely true. In many policy areas, there can be a plethora of trials and academic studies looking at the same intervention but with differing and even contradicting results.

Which ones should we trust? How can we synthesise all this information?

Let’s say we want to comprehensively answer the question “do walk-to-school schemes improve students’ health?”. There are several ways to synthesise the literature and find an answer. But the most rigorous are systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

What is a systematic review?

In a systematic review, a researcher combs through all the high quality, published evidence about a specific intervention and provides a balanced judgement on the effectiveness of that intervention.

A systematic review should be transparent (the methods should be published) and reproducible (someone else following the method should get the same results). Systematic reviews are considered the peak of the evidence hierarchy and the best form of evidence synthesis to inform decision making.

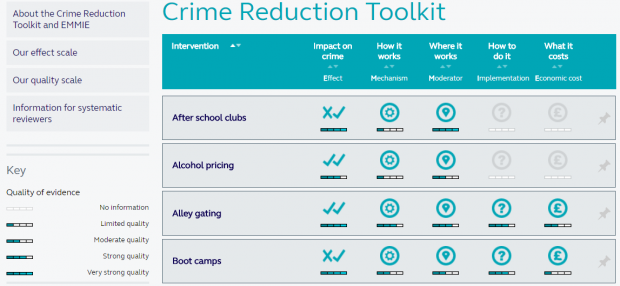

Our network of What Works Centres produce systematic reviews and turn them into accessible guidance or toolkits – catalogues of which interventions are most effective in different policy areas, according to the best studies around the world.

What is a meta-analysis?

A meta-analysis is similar to a systematic review, but takes raw data from different studies asking the same question and combines the data to get a weighted average of the results. The weight given to each study can be altered to correct for weaknesses in individual study design.

When is a systematic review a good idea?

Systematic reviews are big projects: they take an average of 1 year and 2 months to complete1, so they need careful planning and a capable team. For this reason, it’s worth checking registers like PROSPERO and the Campbell Library which list completed and in-progress systematic reviews, to avoid duplication.

A systematic review answers a specific question. Less specific questions, like “What is known about students’ health?” might be better answered by a literature review, which gives an overview of the relevant research on topic. Literature reviews are quicker to conduct than systematic reviews, but they are less rigorous and more vulnerable to bias.

Alternatively, policymakers working on an unfamiliar policy area may want to use a rapid review to familiarise themselves with the gist of recent academic research. There is no agreed definition of rapid reviews, but they are often mini-systematic reviews which omit some steps, cover less literature, and are quickly conducted. Rapid reviews can help policy makers understand which questions to ask and which approaches might work, but they are not thorough enough to provide a definitive answer.

What are the steps involved in a systematic review?

Detailed guidance on doing systematic reviews is available from a range of sources. Cochrane has a Systematic Review Handbook, and PRISMA provides checklists and flowcharts for carrying out and reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

These are the main steps involved in a systematic review:

- Preparation

A systematic review requires a specific research question, and we can use the PICO framework to define it. For example the question “do walk-to-school schemes improve students’ health?” can be refined to consider:

- the group of People the review relates to (pupils in primary or secondary education)

- what the Intervention is (a walk-to-school scheme)

- who is in the Control group (students who do not walk to school)

- and what the measurable Outcome is (whether or not students experienced a change in health indicators, like being overweight).

We also need to define the exclusion criteria, to avoid biased studies, and those that aren’t directly relevant to the research question.

- The search

The next stage is the literature search. This includes searching online databases, such as PubMed or Web of Science, talking to experts to find unpublished data, and studying the “grey literature”, such as think tank papers which are not published in academic journals.

If we only sift through traditionally published papers, we will introduce selection bias. This is because positive results are more likely to be published than null or negative results 2, unfairly weighting published literature in favour of the intervention.

After the literature search, the exclusion criteria are applied. To increase objectivity, two researchers mark each paper for inclusion or exclusion independently (so that disagreements can be resolved by discussion with each other, or with a third researcher).

Next, the data is extracted and the study quality is assessed. Individual studies are scored on their quality and implementation, to reflect how much weight each study should be given: higher quality studies will be more heavily weighted.

- The results

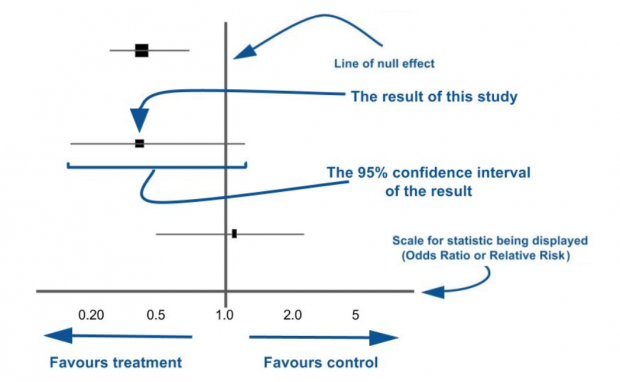

Finally, we can synthesise the data. Themes and concepts can be synthesised in narrative form, noting limitations of studies and the review process. When the question begs a numerical answer, findings can also be synthesised statistically as a meta-analysis, which is often visualised as a forest plot.

Summarising data in a meta-analysis increases its statistical power (the ability to detect the effect of an intervention if there is an effect) and increases the precision with which we know how big the effect is.

Although some groups end the project here, living systematic reviews are ongoing projects, which are updated as new literature is published, so that they remain current and useful.

Leave a comment